The Way Forward #1: From Copenhagen with Covid & Love

This is the beginning of my new series, The Way Forward. It starts with a four-part story about my recent visit to my home country of Denmark, which I left 30 years ago for the U.S. The trip brought me face to face with everything I’d run from and everything I’d given up, and when I got back to L.A. I knew I had to write about it. So I started this blog & podcast series for my paying subscribers who really liked it, and now I’m sharing it with you all. If you want to listen to the podcast version of this where I tell the story, become a paying subscriber for $5. You’ll also get 80 exclusive episodes from the Strangers archive + monthly zoom events and more. Or just enjoy the free blog series, which starts below and continues every Thursday this month. :) Lea

The Way Forward #1: From Copenhagen with Covid & Love

The title of this piece is a bit of a lie, because I’m no longer in Copenhagen and I no longer have covid. I’m back in L.A. and I’m fully recovered, but I did recently spend three and a half weeks in my home country, and I want to tell you about it, because it was a deep existential experience.

Copenhagen may be my favorite city in the world these days, and I’m not just saying that because I’m from there. In fact, I’m not from there. I’m from a smaller city in Denmark called Aarhus, and when I lived in Denmark, I didn’t feel about Copenhagen the way I do now. But the city has changed, and I have changed.

The Denmark I grew up in was far too homogenous for my liking – a stifling mono-culture that made me feel like there wasn’t enough oxygen for me to catch a full breath. Trips abroad felt like much needed infusions from a steroid inhaler, and a month after my high school graduation, I moved to Paris, then to New York, and much later to L.A., where I live now.

In the 30 years that have passed, Denmark has diversified, though still not enough for my liking, and Copenhagen has expanded and internationalized to such a degree that many waiters don’t speak Danish and ask that you place your order in English. Tourists abound, and to some residents it’s almost too much, but I love hearing quips of foreign languages on every corner.

More important, though, than the fact of Copenhagen’s expansion is the way the city has grown: humanely, livably, and even somewhat sustainably, with an emphasis on more bike lanes in a country that already had more bike lane miles per capita than any other country in the world.1

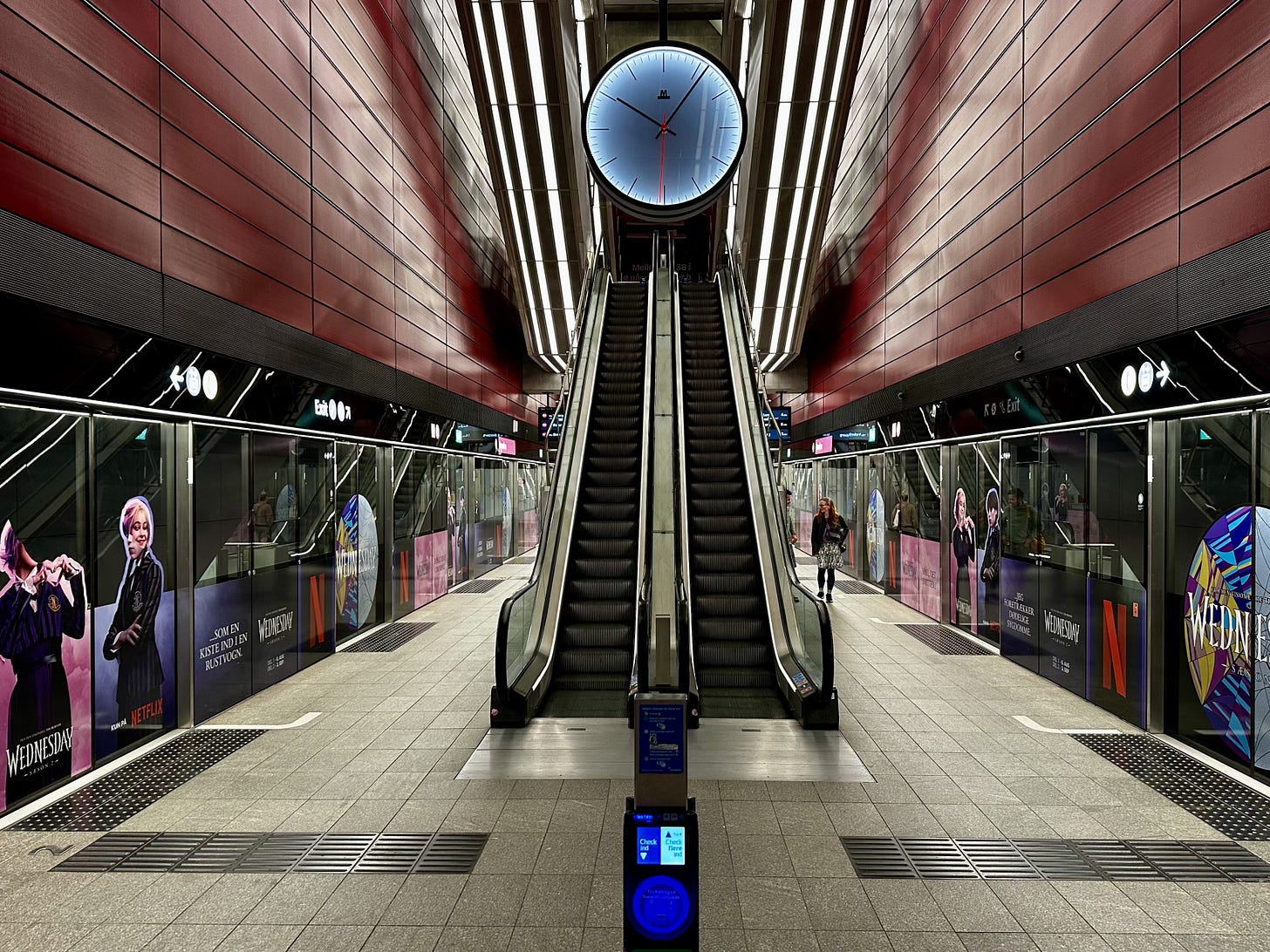

In recent years, they’ve also added a silent, driver-less metro in Copenhagen, and the trains run every two minutes, which means you can leave home 15 minutes before your appointment across town and still make it on time. You can even bring your bike on the metro, of course.

Rounding out the infrastructure improvements in Copenhagen are a number of car-free bridges for bicyclists and pedestrians that crisscross the larger canals. The inner harbor, which stretches deep into some neighborhoods, was once a polluted cess-pool but is now home to a number of so-called ‘harbor baths,’ where you can sunbathe and take a dip.

It wasn’t quite summer when I arrived in early May, but my first day in the city was a beautiful, summer-like day, and I took a walk with my stepmom, whom I stay with when I’m in Copenhagen. She lives in a large, rent-controlled apartment that she used to share with my dad, who died 4 1/2 years ago, behind the socalled New Harbor Canal.

The canal is a popular tourist destination, in part because Hans Christian Andersen lived in one of the colorful apartment buildings, some of which date back to the 1600s, and because of the old sailboats still harbored there, and the many drinking establishments along the canal. We took a quieter street to the Inner Harbor Bridge and walked across to Papirøen, an island in the harbor with street food and boat rentals.

Then we continued over another walk bridge to Christiania, the free town built by hippies in the early 70s at the site of some old army barracks. Christiania has the bucolic charm of a country village mixed with the counter culture vibes of the 1960s, and I managed to buy a little hash there, even though the sale had supposedly been shut down.

Finally we walked across yet another bridge to yet another island, Refshalaøen, full of street food and contemporary art, and we stopped at a cafe on the water’s edge, where people brought their plates and drinks down to the dock. I watched three young topless women share a hummus plate and a bottle of orange wine with their legs dangling over the side of the dock, before they braved the cold-ish water and took a plunge.

Suddenly the idea of returning to the Sexist States of America felt intolerable, and for the first time in 30 years, I had the thought that perhaps I could live in Denmark again.

People have often asked me – do you think you’ll ever go back? – but despite my growing love of Copenhagen and my fondness for the political system in my home country, the idea has always depressed me. Lately though, the political climate in the U.S. and the actual climate in Southern California have made the possibility of leaving L.A. seem more likely than we ever imagined, my husband and I, when we bought our house back in 2016 and thought we’d live there for the rest of our lives.

But if we had to leave, where to?

“Maybe Europe, but probably not Denmark,” I’ve often answered in the past, with a certain the-world-is-my-oyster insouciance because it was all hypothetical anyway.

Now that the question had become real, the idea of starting from scratch in a new place, yet again, sounded more exhausting than exciting, and in this era of global upheaval, perhaps I would be wise to head for a place where I held a passport.

Compared to millions of migrants and refugees who don’t have a homeland to return to, I’m extraordinarily fortunate to have been born in one of the richest, safest, and least corrupt countries on Earth, and I’ve always struggled to explain why I had such resistance to going back there. But in that moment at the café by the dock, where young girls paraded about in nothing but bikini bottoms, and the young boys were too busy discussing world politics to ogle at them, Denmark had never looked better.

The following day, the temperature dropped by 10 degrees Celcius, as it will in Scandinavia even in May, and I left for Sweden to go see the family of my best friend, Anja, who died almost seven years ago. Anja and I lived in the same house as toddlers and we were besties before we could talk. When she moved to a different neighborhood, we kept girlfriend journals, made friendship bracelets, read the same books, and wore matching skirts.

Anja had a mentally ill mother and a series of stepdads who came and went, so she sometimes stayed with us, and she usually spent the summers with me and my cousins at the tiny windswept cabin on the West Coast that my great-grandfather had built.

At 14, Anja was removed from her mom’s care and placed in a group home, and in high school, she dropped out and started dating a druggie who worked on the docks. She found my high school life to be excruciatingly boring and middle class, and I questioned her choices, too, but we still worked in the same restaurant at night, and we stuck together and nursed each other through every emotional bump in the road. Later, when I moved away, she visited me in every crummy room I rented in Paris and the East Village.

The second time Anja came to visit me in New York, I’d found my groove in the city, working at a fun, hip restaurant in the East Village, and I had no desire to go back to Denmark, ever, if I could help it. I was eager to show Anja my New York, and I wanted her to be excited and impressed, but she seemed grumpy and aloof most of the week and it hurt my feelings.

One night we drank at a dive bar on 7th street and we stumbled out at 4am and got in a fight. “Why are you so negative about everything in my New York Life,” I asked, and she said “I hate your New York Life, OK, I hate it!” And then she stormed down the street in the wrong direction, with no intention of slowing down or coming back. This was before cell phones and I wasn’t sure if she even knew my address, so I ran after her and dragged her home by the arm while she screamed, “I hate your New York life!”

Before we passed out on my futon, Anja looked at me with her animal-like brown eyes and said “I hate that you left.”

Anja went back to school and started a career in humanitarian aid that took her around the world, and she married a Swede, while I moved further West from New York to LA. But we stayed connected via skype, and facetime, and phone, and we continued to visit each other in Copenhagen and Brooklyn and Sweden and L.A.

Until October 21, 2018, when her husband called to tell me that she’d suffered an aneurysm by the soccer field while their youngest was playing a game. She was declared dead before I could get on a plane, and I felt like my right arm had been ripped off without anesthesia.

I happened to be in Ohio at the time, and I booked the fastest connection I could get, through New York and Madrid to Copenhagen, crying so hysterically the whole way that two people on two separate flights moved seats to get away from me.

For almost a month after she died, I stayed with Anja's husband and kids, and I never wanted to leave them. I wanted to split myself in two, so I could help raise her boys in Southern Sweden, while also raising my own kids in LA, and for the first time, I felt the real cost of living so far away.

In the years that followed, I visited them every summer, and twice they came to stay with me in LA, but I never overcame the feeling that I was missing a limb when I wasn’t with them. Now the youngest, who was eight when his mom collapsed by the soccer field, had turned 14, and the first reason I’d come to Denmark was to attend his ‘Konfirmation’.

This is a Scandinavian tradition, always celebrated in May, that marks the transition of an adolescent into the adult ranks, and it’s akin to a bar mitzvah or a quinceañera in cultural significance. I would have scaled Mount Everest to be there for it, but all I had to do was take a 10-minute train ride across the bridge from Copenhagen to Sweden, and then another 20-minute train ride to the small village where they live.

When I got there, the boys were taller and more handsome than ever, and a family friend from Denmark had already been cooking for days. We decorated the place with blue and yellow flowers – the Swedish colors – and pretty napkins and lots of candles, and when Saturday came, we welcomed a chosen family of friends and neighbors and relatives and held a beautiful Konfirmation for the boy, whom we’ll call L.

At the dinner, I watched him and his older brother with their friends, and my eyes welled up with tears, not from grief this time, but from sheer joy and relief that they were doing so well and had made it to this place, where they could almost fly on their own.

But during dessert at the Konformation dinner, I started feeling ill. Despite having had no alcohol, I was overcome by fatigue and I had to go to bed at 8 o’clock. The next morning it was clear that I was too sick to stay with them, so I left a day early and went back to Copenhagen, where my stepmom took care of me until she, too, got sick, and we discovered we both had a Covid. For six days I was too ill to do anything, and I had to cancel all plans to work or see friends or family.

The following weekend, I’d invited L, the newly confirmed 14-year-old from Sweden, to come stay with me in Copenhagen, and I was worried I would be too sick for it, but luckily by Friday, I was just well enough to pick him up at the train and take him to a soccer match.

We went to see the Aarhus team, AGF – the hometown team of his mom and me – play an away-game in a suburb of Copenhagen. They played terribly and lost 2-0, but that did not keep the fans from chanting enthusiastically.

As we left, L assured me that it had been a good experience despite the loss. He smiled his shy smile, which reminded me of his mother, and I felt my insides relax. I’d been nervous about the weekend, wondering if he’d be bored with me now that he was 14, almost 15, and whether it would be awkward for us to be one-on-one. But we still seemed to have our old connection, and a sense of peace came over me as we walked out of the stadium with the last glow from the late-setting sun still in the sky.

During the 10-minute walk back to the train, the light turned grey, a wind kicked up, and a fat pigeon hung over the suburban street and cooed – coo-coo, coo-coo. This was a sound that always, instantly, brought me back to Denmark, even when I was 5,000 miles away in a completely different landscape. Now I was on a street that could have been the one I grew up on, or any other suburban street in Denmark – the same red brick houses with privet hedges and flag poles – and suddenly a wave of depression came over me like fog from the ocean on a hot summer day.

Anja and I had experienced this on the West Coast once as kids. Standing on the beach on a beautiful day, we’d watched the fog roll in over the water, like a white wall of smoke. Anja had gripped my arm because it was so tall and almost frightening, and in a matter of minutes, it had nveloped the beach so that we could barely see the water or the dunes, and the air had turned ice cold and fall-like.

Now I was experiencing a similar radical shift, not in the weather, but in my mood, and it wasn’t white, it was dark blue, almost black, but it came on in a similar unstoppable way. Never had a mood felt so heavy, or so physical, or so sudden. It was as if I’d tripped into a well.

“I can’t live here,” I thought. If the coos of a single pigeon could trigger such a wave of involuntary sadness, then how would I ever make it in Denmark?

‘Sadness’ wasn’t exactly the right word, though. ‘Sad’ was what I’d been – beyond measure – when Anja died, and that loss still brought tears to my eyes when I sat down and felt the magnitude of it. By contrast, there were no tears in this well I was in now, no story, and no obvious cause. There was just a feeling of bottomless despair, and my body seemed to weigh 500 pounds.

On the commuter train back to the city, the feeling stayed. The drab lighting in the train car, the stone faces of the other passengers, and the darkening sky over the tile roofs outside didn’t help. L looked at his phone, and I was grateful for it, unable to make conversation from the place I was in.

Back in the city, the lights, the people, and the need to get the boy a kebab helped bring me back. We stopped by Kebabery, a hole-in-the-wall place with a line out the door, and the energy was kinetic and New York-like with Friday night folks of all stripes and colors on their way to or from a bar. It instantly lifted my spirits and we brought the kebab back to my stepmom’s kitchen, where L and I talked until 1 in the morning about life and death and politics. We didn’t agree on everything, but it mattered less in this kitchen than anywhere else in the world, and I only loved him more when he furrowed his brow to disagree with me.

The next morning, all black fog had evaoprated from my inner landscape, but heavy clouds hung over the city. We left the apartment at 10am to embark on a busy day, and twice we got caught in the rain, but we had fun. By the time we made it to Tivoli with my stepsister and her son in the afternoon, the clouds had parted, and Copenhagen looked its very best from the top of the old-fashioned Ferris wheel.

Tivoli is the oldest urban amusement park in the world, and we finished the evening at a booth that has been unchanged since the 1930s where you bet on biking mail men who race around a track. They carry chocolate in their baskets, which you win if they stop at your number.

L and I put 20 kroner on 5, his mom’s birthdate and also my dad’s, whose favorite Tivoli booth this had been. Once when I was a kid, my dad spent more than the candy was worth to win it for me by continuing to bet until we hit, but this time, in our very first round, a heavily loaded mailman came to a stop right in front us at number 5, and we walked off with a big bag of english gummies and a bag of chocolates.

Then we went home and devoured our loot, while we watched the Eurovision Song Contest with my stepmom and laughed our whole heads off at how stupid it was.

It was the perfect weekend.

That’s where we’ll leave the story for today. It will continue in the next installment, The Way Back #2, which will take us to my hometown of Aarhus and drops here in a week, for free. If you’d like to access the first three chapters right now, also in audio form, scored by my husband, Paul, become a paying subscriber for $5 today. Episodes 1, 2 and 3 are bingeable – and readable– now! Or, if you can, please consider becoming a founding supporter at $100 per year (=$8.30/mo). You’ll receive additional bonus content and other benefits, and you’ll help me make more stories – a win-win if you ask me!

Thanks to my story editor, Christina Thyssen, and my Assistant Producer, Vix Jensen, and to all of you for being here and reading along. I’m grateful for your time and I welcome all feedback, comments, and discussion.

It was hard to find a straightforward statistic on the number of bike lanes per capita in different countries. From my research, I gathered that The Netherlands had the most miles of bike lanes of any country, but they also have three times the population of Denmark and when I did the math of bike-lane-miles divided by population, Denmark came out on top. It’s a bit of a homemade stat, though.

I’m not able to comment on Part 2 on Aarhus (pay-gated?) but I just wanted to say I’m enjoying this series so much. Much is deeply relatable - the way our relationships with our parents fissure and change as we age, how hard it is to replicate friendships from childhood. You write in such a deeply warm way about the people you love, I can feel it through the screen. Can’t wait for part 3!

Was really compelled reading this first wonderful chapter.